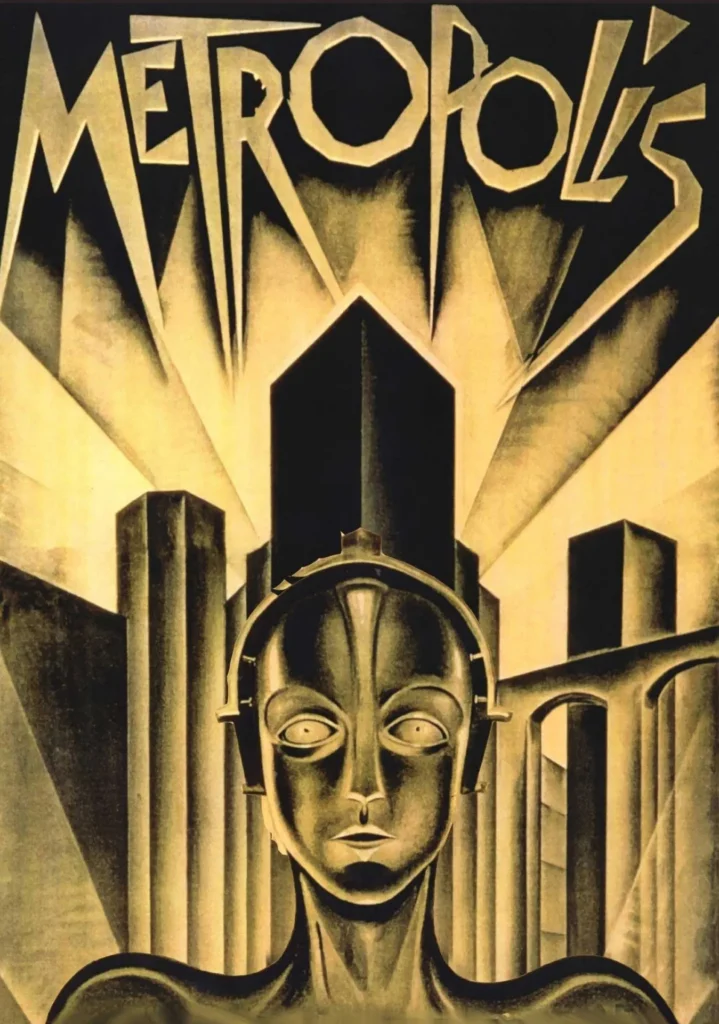

When people talk about Fritz Lang’s Metropolis, they often do so with awe; the towering skyscrapers, the hypnotic machinery, the cinematic grandeur that defined an era.

But from an architect’s point of view, the city of Metropolis isn’t visionary. It’s a warning.

Lang’s film is not a celebration of progress; it’s a blueprint of oppression disguised as futurism. Beneath its shimmering façades lies an idea of architecture that mistakes hierarchy for order and monumentality for meaning. Watching it almost a century later, in the age of smart cities and algorithmic design, we need to ask not what Lang predicted, but what he misunderstood.

Here’s a deep dive into the movie for 2000s kids who’ve never seen it or have only just discovered this masterpiece.

Table of Contents

1. Architecture as Destiny: The False Promise of Order

Released in 1927, Metropolis was the first film to imagine the city of the future on such a grand scale. Its streets hum with machines; its towers pierce the clouds; its society is divided between a pampered elite above and the labouring masses below. The film presents architecture as destiny: a vertical social order cast in concrete and steel.

For architects, that’s precisely the problem.

Lang’s Metropolis shows a city conceived as a single, total system, visually stunning, socially catastrophic. It’s a city drawn not to be lived in, but to be obeyed. No informal growth, no spontaneity, no porous edges, just total design from above. Architecture here isn’t a language of coexistence; it’s a grammar of control.

Real cities grow through mistakes, negotiations, and adaptive reuse. Metropolis denies all of that. It’s a fantasy of perfection that reveals the authoritarian temptation behind architectural totality.

2. The Architectural DNA of the Film

The city’s visual structure reflects the artistic movements of its time:

- Art Deco: the polished symmetry and vertical emphasis of the upper towers, echoing Manhattan’s emerging skyline.

- German Expressionism: the exaggerated scale, the emotional lighting, and the distorted perspectives that transform space into psychology.

- Industrial Futurism: endless elevators, conveyor belts, and monorails that turn motion itself into architecture.

- Gothic and Biblical forms: spires and arches that make industry feel like faith, especially in the Machine Hall, which functions as a perverse cathedral.

It’s easy to admire this synthesis, but as urban design, it’s dystopian. The film’s aesthetic unity becomes social rigidity. The city’s architecture is the physical manifestation of ideology: rigid, hierarchical, and absolute.

3. Architectural Inspirations Behind Metropolis

Lang didn’t invent his futuristic city out of thin air. When he began filming Metropolis in the mid-1920s, the world was already captivated by modernist dreams of the mechanised city, an urban order where architecture would rationalise society. The film’s skyline is, in fact, a cinematic collage of the most radical architectural ideas of its time.

1. Le Corbusier’s “Ville Radieuse” and the Vertical City

Although Ville Radieuse (Radiant City) would be published a few years later, Le Corbusier’s earlier writings, especially Vers une architecture (1923), were already circulating among European designers.

Lang’s towers echo Le Corbusier’s obsession with vertical zoning: separating living, working, and leisure spaces through height. The crystalline symmetry of Metropolis’s skyline resembles Le Corbusier’s towers-in-the-park concept: monumental, rational, but socially sterile.

Both share the same flaw: the erasure of street life and spontaneity in favour of order and control.

2. The American Skyscraper Boom

In 1924, Lang and his wife, Thea von Harbou, visited New York City, and that trip shaped Metropolis more than any book. Lang described standing on a Manhattan rooftop, watching the lights of the city and the movement of elevated trains, feeling “as if the buildings were a vertical symphony.”

The film’s monumental towers and layered traffic routes clearly borrow from Manhattan’s emerging skyline: the Woolworth Building, the Equitable Building, and early concepts for the Chrysler Tower.

Yet, while New York’s verticality expressed commercial dynamism, Lang turned it into a metaphor for oppression. Metropolis transforms Manhattan’s optimism into a nightmare of stratification.

3. German Expressionist Architecture

The distorted geometries of architects like Bruno Taut (Alpine Architektur, 1919) and Hans Poelzig (The Golem set designs, 1920) strongly influenced Lang’s production designers.

Expressionism treated architecture as emotion frozen in form: crystalline, symbolic, and theatrical. In Metropolis, those principles became literal: buildings pulsate with psychological tension, their exaggerated scale mirroring the inner turmoil of the film’s world.

4. Futurism and Industrial Aesthetics

The Italian Futurists, especially Antonio Sant’Elia’s “Città Nuova” (1914), imagined a mechanised metropolis of dynamic movement, bridges, and overlapping infrastructure. Lang’s city looks like Sant’Elia’s sketches brought to life.

But where Sant’Elia saw heroic progress, Lang saw dehumanising repetition. The machines don’t liberate; they devour.

5. The Tower of Babel and Neo-Gothic Revival

Lang’s inclusion of the Tower of Babel sequence ties modern architecture to ancient myth. The city’s central “New Tower of Babel,” headquarters of the ruling class, fuses skyscraper modernism with Gothic symbolism, a cautionary reminder that human ambition, not technology, is the real catastrophe.

This mix of modern form and medieval morality gives Metropolis its strange timelessness: it looks futuristic, yet spiritually archaic.

6. Industrial Architecture and Early Modern Factories

The film’s underworld: the Machine Halls and tunnels, draws directly from the industrial architecture of early 20th-century Germany, particularly the AEG Turbine Factory by Peter Behrens (1909).

Behrens’s vast glass and steel interior, designed to glorify labor and technology, becomes in Lang’s hands a dystopian altar. The resemblance is deliberate: both structures are cathedrals of production, but Metropolis strips away the utopian promise.

4. The Vertical City: Hierarchy Made Stone

Lang’s urban composition is a literal class diagram.

At the top, the ruling class lives among the clouds, bathed in light. Deep below, the workers toil in mechanical catacombs: a subterranean hell. Between them lies a mediator, the hero Freder, tasked with reconciling “the head and the hands.”

That motto, however, collapses under architectural scrutiny.

In Metropolis, space enforces social structure: verticality equals power. The “head” rules because it is physically elevated; the “hands” suffer because they are buried. This is urbanism as a caste system.

Modern cities still struggle with that vertical symbolism: penthouses versus service basements, financial cores versus peripheral labour zones. Lang’s film exposes a truth architects still face: every floor plan is a political statement.

5. The Pseudo-Sacred and “Utamoh Thumo” : The Highest Darkness

In a scene, the inscription “Utamoh Thumo” appears on a building, a phrase that looks ancient but belongs to no real language.

It’s most likely invented, yet it resonates with a Sanskrit echo: uttama tama, literally “the highest darkness.”

That paradox could summarise the film’s entire philosophy.

Lang’s metropolis worships light, progress, and machinery, but the closer we look, the more those symbols darken. The city’s most sacred space, the Machine Hall, mirrors a cathedral nave. Workers move rhythmically like monks in a ritual, but the object of devotion is an engine. The architecture converts faith into function, sanctity into servitude.

“Utamoh Thumo” — the highest darkness — is thus an apt metaphor.

6. Architecture as Psychological Machine

Lang’s buildings don’t just contain people; they manipulate them.

- Alienation: the workers’ spaces obliterate individuality. Their synchronised movements and confined corridors reduce them to components. Architecture becomes an instrument of psychological conditioning.

- Awe and submission: the monumental towers of the ruling class dwarf human presence, turning admiration into obedience. Scale becomes social control.

- Ritualised suffering: the Machine Hall’s religious geometry turns labour into liturgy — pain rendered as purpose. It’s no accident that when the machinery fails, it morphs into a demonic idol, consuming the workers it commands.

For the characters, these spaces produce despair and detachment. For the audience, they create ambivalence: we are enthralled by what we should condemn. Lang weaponises architecture not just inside the story, but against the spectator’s moral distance.

7. Expectation vs. Reality: What Actually Happened

A century after Metropolis, the future did not unfold as Lang imagined. Instead of a single unified monumental style, modern cities grew into patchworks of overlapping eras and aesthetics. The strict vertical segregation he depicted has softened into a blur of physical and social boundaries, and the grand machinery that once stood as the civic heart has been replaced by infrastructure that is digital, dispersed, and largely invisible. Far from achieving total aesthetic control, today’s urban environments are fragmented, adaptive, and increasingly shaped by citizens themselves. And rather than reaching a state of rational perfection, cities now operate within ecological complexity, improvised, dynamic, and often delightfully messy.

In other words, Metropolis imagined that architecture could impose total order. Reality proved that livable cities thrive on disorder. Our actual urban landscapes: Tokyo, São Paulo, Lagos, and New York, are far more resilient precisely because they are messy, layered, and alive.

8. Psychological Impact on Spectators

Why, then, do viewers still find Lang’s city beautiful?

Because it satisfies two conflicting desires: the wish for total order and the fear of losing freedom. The city on screen allows us to experience both at once: admiration and anxiety. Its architecture hypnotises us into complicity, inviting us to enjoy what we would never want to inhabit.

This ambivalence is why Metropolis endures. Its aesthetic power neutralises its moral warning, a phenomenon that architectural critics, from Siegfried Kracauer to Susan Sontag, later recognised: the beauty of control can disguise the ugliness of obedience.

9. Major Architectural Critiques Through History

- Siegfried Kracauer (1930s): In The Mass Ornament and From Caligari to Hitler, Kracauer saw Metropolis as the prototype of mass choreography, where architecture and spectacle merge to prepare the mind for authoritarian order.

- Production Historians (Bergfelder, Film Architecture and the Transnational Imagination): the film’s design team (Kettelhut, Hunte, Vollbrecht) built a city of stylistic pastiche, more cinema than urbanism. The sets were meant to impress, not function.

- Tängerstad’s “Cathedral and Skyscraper” (1990s): interprets the Machine Hall as an expression of industrial theology, arguing that Lang’s architecture fuses religion and technology to naturalise power.

- Urbanist Readings: Later critics treat the film as projection, not prophecy, expressing Weimar Germany’s fear of industrial capitalism and American skyscraper modernity.

- Contemporary Reassessments: Modern scholarship warns that Metropolis’s imagery influenced both democratic modernism and totalitarian aesthetics. Its visual clarity became a model for architecture’s capacity to awe, and therefore to dominate.

10. Lessons for the Modern Architect

If Metropolis teaches anything, it’s that architecture without empathy becomes architecture against humanity.

Lang’s city is perfectly designed, and perfectly inhumane. It demonstrates how easy it is for design to slide from utopia into authoritarian choreography.

Today’s architects face subtler versions of the same temptation: the dream of “smart” totality, of algorithmic order, of seamless efficiency. But cities, like people, thrive on contradiction. They need space for unpredictability, failure, and dissent, the very qualities Lang’s city erased.

11. The Future We Refused

Fritz Lang imagined a future of steel and control, and in doing so built one of cinema’s most seductive nightmares.

Almost a century later, his Metropolis remains less a prophecy than a psychological x-ray of modernity, showing how easily architecture can transform from art of shelter to instrument of power.

We can still admire its craft, but we should not mistake it for vision.

Lang’s city is not the city of tomorrow; it’s the mirror of a century’s anxieties about technology, hierarchy, and the loss of the human scale.

As architects and urban thinkers, our task is not to replicate that grandeur, but to dismantle the ideology behind it; to build cities where the “darkness” finally gives way to light.